Go to comments.

P-adic Visualizations

Go to comments.

How do we calculate how far apart numbers are?

This would seem to be an easy question to answer: just subtract them. 5 and 2 are 5 - 2 = 3 units away, whatever we’re counting. And most of the time, it’s the best answer.

But this a distance that relies mainly on addition and subtraction. There’s another sort of distance which is more closely related to multiplication, division, and cycles.

To get a taste of this sort of distance, let’s take hours on a (12-hour) clock. How far apart are 1 and 2? 1 hour. This is the same whether we’re talking about 1 hour of real time passing, 13 hours, or 145 - on the clock, we wrap around every 12 hours. Cycles are a common part of our life; additive and subtractive distances assume that everything can grow infinitely apart, but those aren’t the only sort of distances in our experience.

This sort of clock arithmetic, “modular arithmetic”, is an interesting subject in itself. But sometimes in nature, things aren’t quite cyclical; they look almost like cycles, but then if you zoom in, you’ll see additional cycles hanging out on the original cycles. P-adic distances take modular distances a step farther: we can have our cycles, then cycles on cycles, then cycles on cycles on cycles. (Cue a “Yo Dawg” meme here.) We want to be able to refine our analysis at every level. So let’s begin our descent.

(Specifically, p-adic numbers use prime cycles, hence the p-. So we’ll have 3-adic, 5-adic, 7-adic, but not 6-adic numbers. But the reasons why won’t be relevant to the discussion here.)

Cyclical Refinements

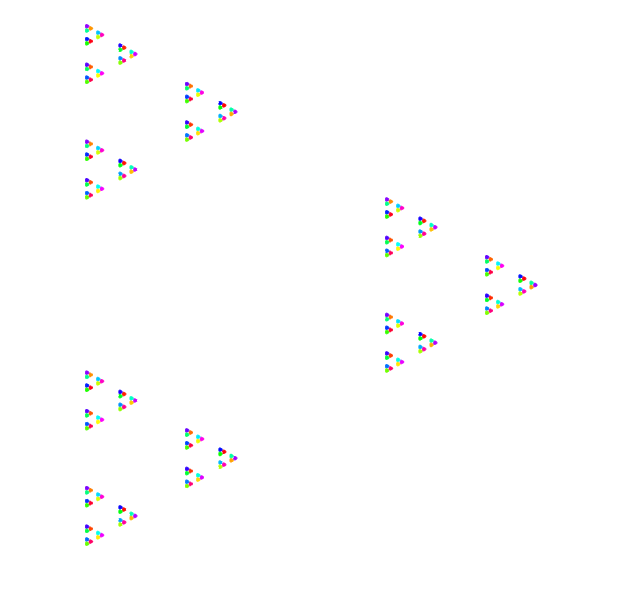

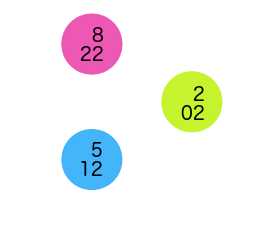

Let’s work with 3-adic numbers:

As one might expect, everything is in threes. The main idea is this: first, we take a number (say 29) and calculate what it is modulo 3 (that is, what the remainder is when divided by 3). This is 2. This first step will take us a distance of 1 from the center, angled toward the top. (Why 1? 1 is simply the basic unit everything else is compared to; aside from making certain equations work out nicely, it’s a good starting point when we don’t quite know what’s coming next.)

A number like 10 which is 1 modulo 3 would be angled toward the bottom triangle, and any clean multiple of 3 toward the rightmost one. (The precise angles are unimportant, as long as we can space them in thirds around the center.)

But unlike modular arithmetic, we don’t stop there. That’s just the information we got from the first cycle of 3s; what about the next one? That is, how do these numbers compare with regard to 3*3, and 3*3*3, and so on?

We start by representing each number in base-3. So 0 is 0, 1 is 1, 2 is 2 … then 3 is 10. 10 is 101, 29 is 1002. Normally, we represent numbers in base-10, so the furthest digit right is the 1s place (10^0), then the 10s place (10^1), then 100s (10^2), and so on. Other bases work the same way, building off of powers of the base. So in base-3, we have a 1s place, a 3s place, a 9s place, a 27s place, etc.

So why is 29 written as 1002? Well,

- 2 is in the 1s place,

- then we have 0 for the 3s and 9s places,

- followed by 1 in the 27s place.

So, 2*1 + 0*3 + 0*9 + 1*27 = 29.

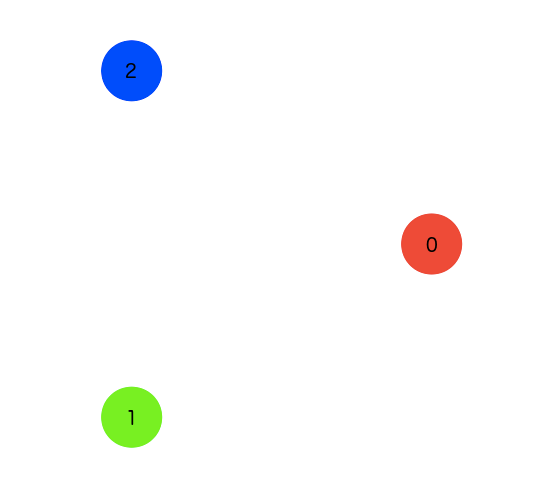

The digit furthest right gives us the first triangle destination:

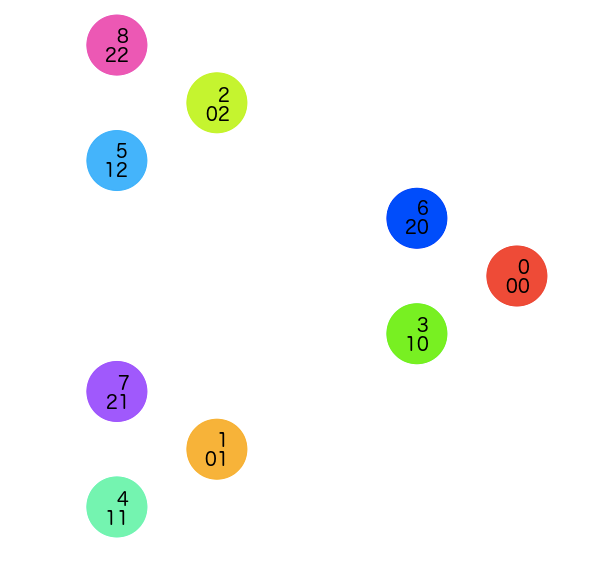

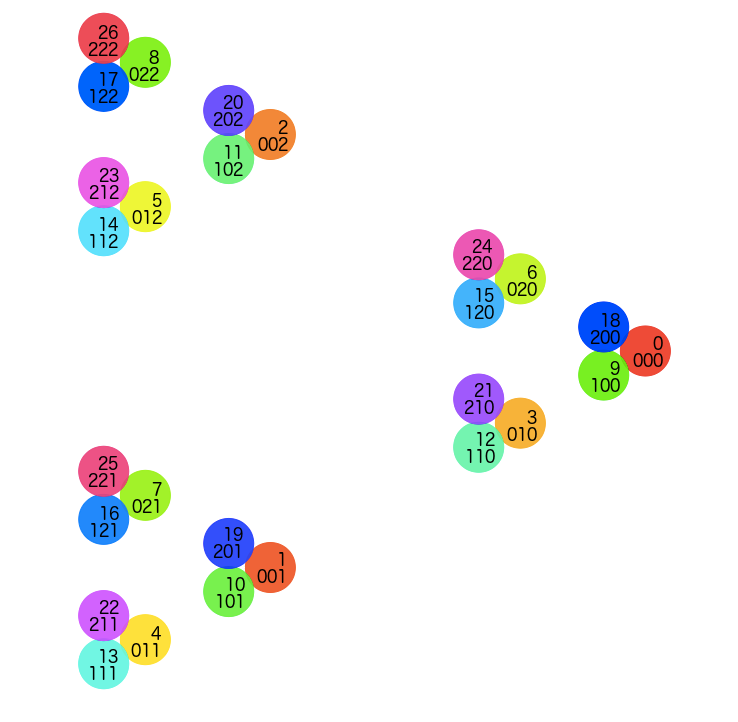

then the next digit gives us the triangle inside that triangle (numbers written in both base-10 and base-3):

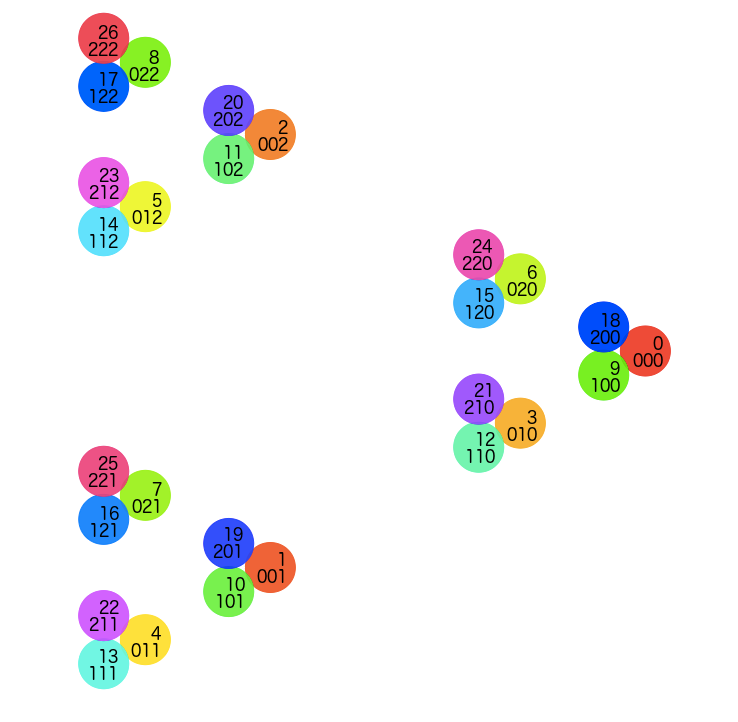

then the triangle inside the triangle inside the triangle:

as far as we want to go.

Representing numbers in different bases isn’t all that unusual, however. That would leave these the same old numbers as always, just with funny costumes. What we’ll be doing differently is that, with each digit left we traverse, we’ll make our steps smaller. Normally, we think of changing the 10s place as being much more of an event than changing the 1s place, with the 100s place even more so. And with our normal additive and subtractive distances, that is true. But we’re looking at cycles here.

The first cycle, given by our number modulo 3, is the biggest sorter of numbers. After that, we’re making continual refinements - 6 and 18 are both multiples of 3, so are more like each other than either is to 7 in that regard, but 18 is also a multiple of 9, which makes it three-ier than 6. It not only can come back to the start if we wrap it around a clock with 3 hours, but also with 3 of these 3-houred clocks. 54 can manage 3 cycles of 3 cycles of 3. But none of these tricks matter if the a number can’t be a simple, homespun multiple of 3 in the first place.

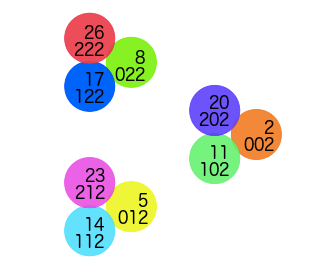

This concept of refinements also leads to a principle of coherence. Let’s take our second level of triangles again:

5 is 12 in base-3 notation (2 in the 1s place, 1 in the 3s place, to give 2*1 + 1*3 = 5). Now, we add another layer:

Take a look at the dots surrounding 5 (12). We just prefix each one by a different digit:

- 5 = 012 (putting a zero in front doesn’t change the number)

- 14 = 112

- 23 = 212

As we zoom in, we add our new digits to the left, but everything in that spot will share the same base digits. You can check this out with the triangles starting with 2 and 8 as well.

So at each step, we tweak our numbers a little more. We take our triangles, and separate them out into triangles, and separate those out into triangles. The farther left we go in our digits, the smaller the distances become, and the closer our new triads of numbers will be in 3-adic distances. This is what will create new numbers for us.

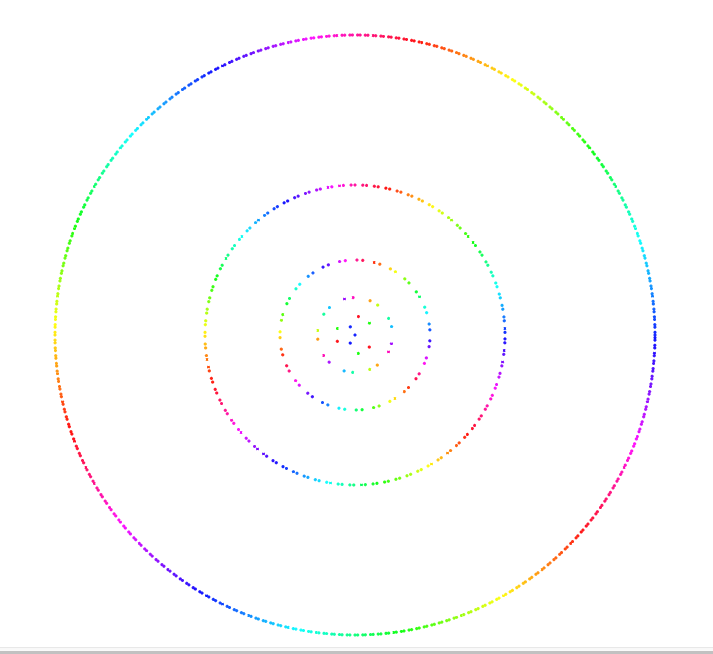

(We can also view these numbers around a circle, the radius given by their 3-adic distance from 0:

To try out different norms and to watch them animate as numbers flow from one to the next, go to: https://nomicflux.github.io/PadicVisualization/.)

New Numbers

Normally with numbers, we can create fractions; this gives us the rational numbers. Then we “fill the gaps” between those fractions; that is how we get the irrational numbers, like pi. We can find the cracks in between any two fractions, and go one level deeper; if we follow all these paths left in between the cracks, we can end up with a completion of the rational numbers.

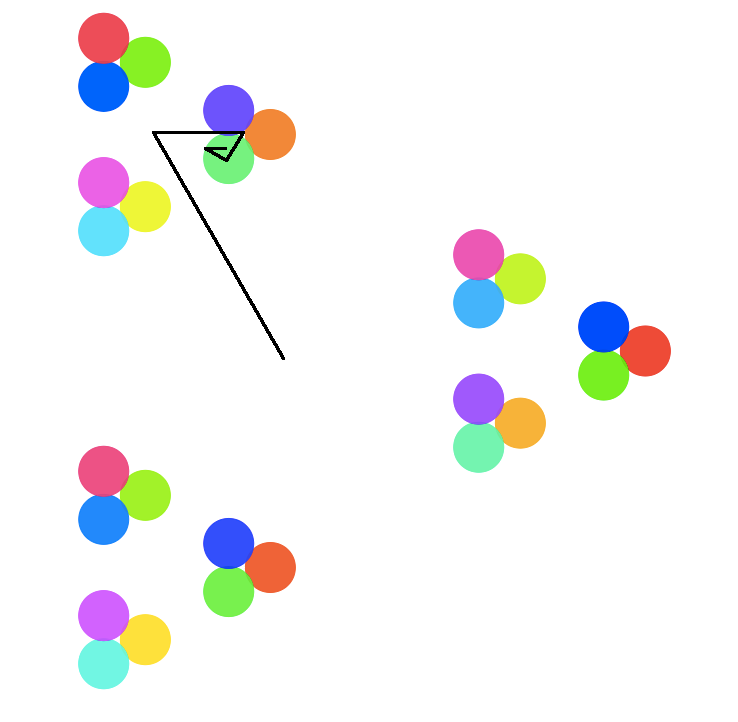

P-adic numbers have their fractions too, which I won’t get into here (in the visualization, think about being able to zoom out one extra set of triangles at a time; we can do that any number of times, but this doesn’t change the overall picture much. We’ve just added another level of triangles in a stack that’s already triangles all the way down). Remember, sizes and distances are given by how close the numbers are concerning cycles of 3 (or 5, or 7, or other numbers we might be using for comparison). So when we complete this system by filling in the cracks, we won’t be working our way between fractions in the same way. We’ll be finding numbers yet three-ier (five-ier…) than have been found before, charting new paths within:

The distance between, say, 4 and 2 is 1 (to start with a baseline); they are not even in the same starting triangle (or equivalently, when we write them in base-3 as 11 and 02, their rightmost digits do not even agree, and so when we subtract 02 from 11 we get 02). This is also true of the distance between 100 and 2 (where 100 is 10201: 1*1 + 0*3 + 2*9 + 0*27 + 1*81). 5 and 2 are in the same starting triangle, though; 5 - 2 is 3 (in base-3, 12 - 02 = 10), but the distance will be closer than 1. So we’ll say it’s 1/3 (the important part is just that it must be smaller than 1 so that the numbers are closer, more three-ly together; again, think about refinements on a starting position).

11 - 2 is 9 (base-3: 102 - 002 = 100), which being 3*3 must give an even smaller distance: 1/9. This means that 2 and 11 are not only in the same starting triangle, but the same second-level triangle. The distance between 20 and 2 is also 1/9; 20 - 2 = 18 (202 - 002 = 200) which similarly places them in the same second-level triangle, since 18 is a multiple of 9.

So remember that as odd as this new distance seems, it translates literally into how close the numbers are in the visualization:

To fill out our paths, we’ll need to extend the numbers outward to the left, exploring numbers which in regards to three-iness are always going one triangle deeper in than what we have. We can extend this to infinity, just like we would keep going to the right with decimals, such as with 3.14159… to get pi.

When we simply wrote our numbers in base-3, they were the same numbers donning tri-corner hats. When we changed the way we calculated distances between them, they started getting a little odd, perhaps imbibing too much at the math social. Now, however, we have created an entirely new set of numbers, by tracing paths deeper and deeper into the triangle abyss. Our tipsy digits have launched an expedition to the Pacific and found the ruins of R’lyeh with all it contains. These eldritch numerosities simply do not exist in the mundane number system. They cannot be created in it, cannot be represented in it.

(I will not explore the following point more in this article, but in addition to spawning numerics from outside our Euclidean topologies, we have created a number of numbers that we already know. For example, in 3-adic numbers written in base-3, what would be ….22222 + 1? Carrying the 1 out to infinity, we get: 0. ….22222 is then -1. Starting from nonnegative integers, we have gotten negatives for free. This should look familiar to computer people: in 2-adic numbers, -1 would be ….11111, an infinite two’s complement. If you play around a bit, you can find that we also have numbers we would have regarded as fractions in our normal numbers, but constructible as these infinite integers. See if you can find a number x such tha 5*x = 1 in 3-adic numbers; this makes x a 3-adic version of 1/5.)

Continuous Analysis

This completion of a p-adic number system allows for something quite unusual: we have created a continuous number system (of course, mathematically, that was what we were going for; a system where all Cauchy sequences converge). We can do calculus with these new numbers, using most of the rules we may have learned and lov… well, learned once upon a time.

The reason this is so weird, however, is that our p-adic number system is entirely based on how divisible numbers are. We have taken the concept of breaking down numbers into discrete chunks, entirely concerned with the whole blocks we can make from counting and use to make numbers, and made it analyzable by techniques entirely concerned with infinitesimal but continuous changes and their impact. P-adic numbers unite these disparate mathematical disciplines, granting us access to a new toolbox which shouldn’t work, but does. It’s like finding a way to turn a philosphy degree into a paying, non-academic job. (Before the hatemail arrives, this is a point taken from personal experience.)

I will give one example before closing out this post. Around Calculus II in the US curriculum, we start learning about series. In particular, there are the Taylor and Laurent series of a function (wikipedia refresher here). These series allow us to take a function and analyze it at a single point. We first look at the value of the function at that point, then we take the tangent line at that point using the first derivative - that is, we find the line which is the best approximation a line can be to our function at the point we chose.

We keep adding on derivatives to further nuance our approximation, using the information that we have about how the function curves, then how the curve curves, and the curves on the curves on the curves. It is like being an ant on the function, trying to reconstruct the entire curve based just on the nuances available right around you. Some functions lend themselves well to this analysis; others will give very different approximations based on how they look from different points.

The key takeaway is that we can analyse functions locally to get a picture of the whole from that point. P-adic numbers are effectively doing the same thing with numbers; instead of derivatives, we use divisors. Instead of tracing the curves on curves at a point, we are tracking the cycles on cycles. (This is not just a metaphor; this insight is behind the creation of the p-adic numbers originally.)

Other works on the p-adic numbers will dive in deeper starting with this insight. My point in this post is to have generated some of the intuitive, visual appreciation for these oddities, and to provide a launching pad for further study.

Return to post.