Go to comments.

The co-intuitions of cointuitionism

Go to comments.

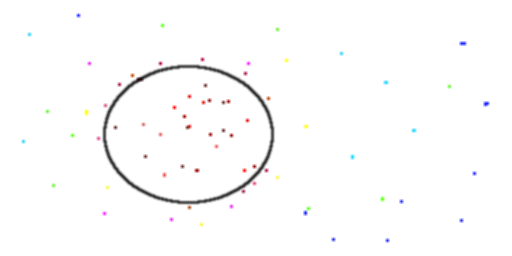

Let’s look at the following image:

We’ve got some red things in the middle, and some non-red things around them. But what happens in between?

Classical logic says: there is no middle. There’s no gap between red and non-red (the law of the excluded middle) and there’s no overlap (the principle of non-contradiction).

Another alternative is intuitionistic (or constructivist) logic, which states: There’s what’s provably red, and what’s provably not-red, and then some undecidable middle ground. In other words, the law of the excluded middle fails. But the principle of non-contradiction is, if anything, even more unimpeachable than in classical logic.

But when it comes to mathematics, we often get a dual notion for free, where everything is run backwards. Usually we use the prefix co- to denote such dualities, and this case is no different: there is also a co-intuistionistic logic. The law of the excluded middle holds, but the principle of non-contradiction fails. We get red, not-red, and a boundary region of red-and-not-red.

In this post, I’m going to set out some of the differences between these logics, and why it might be interesting to study a logic which allows contradictions.1

Classical Logic

First off, what would classical logic say about the boundary between red and non-red? What’s in the middle?

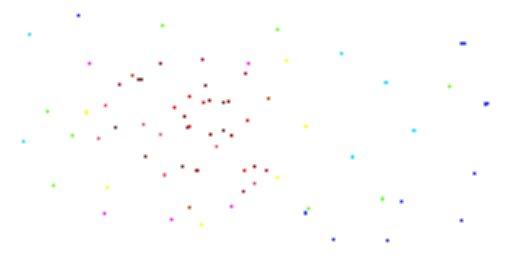

Classical logic would say that that circle I drew above is a fiction.2 It doesn’t exist. We just have the dots:

There’s just red and non-red dots. Sets of things are merely what they contain. So there is no boundary. But surely we can get closer and closer and closer to being red, until it’s ambiguous as to whether we are red or not, right?

In classical logic, that would just mean that “red” is not a precise enough term. We commit the fallacy of equivocation: we are trying to use “red” in multiple senses, from a deep scarlet to rust to colours verging on burgundy and blood orange. If we want to use classical logic, we need a precise notion of “red”: an exact range of wavelengths, perhaps, or a set of HTML codes, even if it just contains #FF0000. (And remember, there is absolutely nothing more to that set of HTML codes than just the HTML code(s) themselves; it is an exact list, and anything in is in while anything out is out).

When we do have precise terms, and we know that they apply to something real which we can ask questions about, this is reasonable. But is that always the case?

Logic is supposed to be a measuring stick for thinking. Classical logic focuses on the “measuring stick” part, but one could say that we need a logic for the “thinking” part as well. It may not even be possible for words to be made precise enough for classical logic, and some views of the nature of reality would deny that there is anything to be picked out with such precision (either because it’s all ultimately One, or all in flux and changing, or there is no way of getting outside of our conventional ways of thinking and speaking). So whether we want other logics for particular uses, perhaps to explore the notion of Truth in more ways, or whether we think that there is no actual use for classical logic, the following alternatives offer us a larger picture.3

Intuistionistic Logic

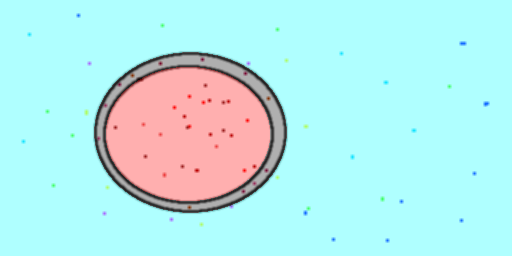

Intuitionistic logic is a logic of gaps, and a logic of what can be verifiably proven either true or false vs. what can’t be decided. Returning to the picture from earlier, we have the following:

Here we have dots which are very clearly red. Then we also have dots which are very clearly non-red. But then we also leave open a gap in the middle.4 There is the “undecidable” region as well.

Alternatively: think of a unicorn. What colour is it? Does it have stripes? How long exactly is its horn? What is its genome, and how similar is it genetically to a liger? At some point, you probably don’t have an answer. Moreover, there’s no way to come up with an answer, because unicorns don’t exist (retroactive spoiler alert) so they can’t be studied, and at any rate the one in your head most certainly does not exist.5

Mathematics potentially has similar issues. We can prove that there are different sizes of infinities; but is there an infinity between every such pairs of infinities? This is a simplified form of the Continuum Hypothesis.

Again with infinities: if we have an infinite number of sets, can we arbitrarily pick one element from each set? This is the Axiom of Choice, with its equivalent cousins the Well-Ordering Principle and Zorn’s Lemma.6

The common thread is that we can’t prove or disprove any of these statements from our normal foundations. We can accept the Axiom of Choice and the Continuum Hypothesis, or we can choose to reject them, without being inconsistent with the rest of mathematics (roughly and simplistically speaking). Similarly, we can say that unicorns are really mutant ligers with minimal genetic differences from them, or that they are the ligers’ genetic opposites (and sworn enemies). There is nothing in our experience which can prove this one way or another.

So that does it for gaps and the undecidable. But wait, there’s more!

Cointuitionistic Logic

Much less studied than intuitionistic logic is cointuitionistic logic. One way of thinking about the difference is this: Intuitionistic logic starts with nothing on the table, then puts forth some basic things that are true. From that, it only allows what we can prove or disprove from those basic points. It is a minimalistic logic, guarding the necessity of inferences.

Cointuitionistic logic is the mirror image: We start by assuming that everything could potentially be true (which means that it could be true that unicorns are related to ligers and could be true that they are not), except for some basic things which we can subtract out. The subtraction part is new: unlike classical and intuitionistic logic, which discuss the possible inferences we can make to extend our knowledge, cointuitionistic logic starts assuming everything. We don’t infer new truths, we subtract out what we have seen cannot be the case. “True”, speaking cointuitionistically means we can’t prove we can subtract something out from our view of the world, and “False” means we can’t prove that we can subtract out its negation.

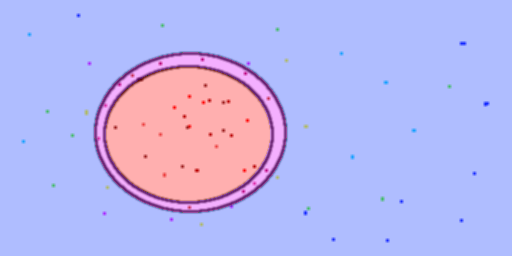

Ok, that’s getting pretty wonky. Time for a picture break:

Red and non-red overlap. We find some dots for which we can quite clearly subtract out the notion that they are not red. Similarly, on the other extreme, we can clearly subtract out the notion that other dots are red. In the overlap, however, we can’t clearly subtract out either.

Cointuitionistic logic is the logic of boundaries, of overlap, of regions of contradiction which don’t infect the entire space. It is a maximalist logic, trying to keep hold of everything which could possibly turn out to be true, even if that means holding on to inconsistencies.

Back to our discussion of fiction: can dragons fly? Yes and no. There are possibilities for flying dragons and non-flying dragons; not merely in the sense that there could be different species of dragons, but also in that dragons don’t exist (retroactive double spoiler alert) so they have conflicting properties.

Now, fiction seems like an easy target, and perhaps not worthy of logical analysis. Of course we can say anything we want. But not all constructions are pure story; we deal with and have to make decisions about all sorts of cultural constructs, including laws, standards of politeness, social interactions, identities (professional, gender, etc.), and so on.

One reason for studying a logic which allows contradictions is the Principle of Explosion. In both classical and intuitionistic logic, if you can ever prove a contradiction, then you can prove anything. But like I said above, logic is a measuring stick for thinking, and oftentimes our thinking comes to contradiction. Maybe I think that there is strong evidence for A, and also strong evidence for B, but A leads to consequences which contradict the consequences of B (I’m leaving this general, to avoid picking sides on any troublesome issues, but feel free to substitute any moral and/or political dilemmas which you feel torn between). Cointuitionistic logic gives a space for those contradictions to exist, with both sides being held in discussion at once, while leaving open the possibility of debate and inference about clearer issues outside of the contradictory boundary.

Conclusion

This post has just been a short introduction to these different logics. I plan to talk about them more in the future. But to wrap up, here’s a chart of their differences:

| Classical | Intuitionistic | Cointuitionistic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nature | Unambiguous and Precise | Minimalistic | Maximalistic |

| In-betweens | Don’t Exist | Undecidable Gaps | Overlapping Boundaries |

| “Truth” | Just What Is | Provable Inference | Lack of proof of subtraction |

| Scope | Simple Existence | Necessities | Possibilities |

| Unicorns v. Ligers | Ligers | Bertrand Russell | Uniligers |

[1]: N.b.: For the logicians and pedants amongst you (not that I have a proof of existence for the latter!), this is an exploratory post, a place for me to put down my thoughts, and an exposition where I try to set down the basic intuitions (pun half-intended) for the different logics. I do plan on adding more precision and rigour in future posts. ↩︎

[2]: Technically, these different logics are systems of rules. I’m applying interpretations to them, to show what they could mean and how they might be used, but the algebraic patterns and rules of inference are what are basic. ↩︎

[3]: Even if one is perfectly satisfied with classical logic, intuitionistic and cointuitionistic logics form perfectly valid, rigorous, and precise patterns in their own right - see Heyting and Co-Heyting (or Brouwerian) algebra for more details. ↩︎

[4]: An astute reader might notice that a gap doesn’t solve the problem. Where do we draw the line for the “undecidable” region? If you thought this, have a cookie. If you didn’t, also have a cookie, because cookies are delicious. Think of red / non-red as an analogy, a ladder to be disposed of once you have climbed it. ↩︎

[5]: Well, depending on your views on the existence of fictional entities. ↩︎

[6]: A mathematical joke goes: The Axiom of Choice is obviously true, the Well-Ordering Principle is obviously false, and about Zorn’s Lemma, who can say? The joke is that the three are all equivalent, in that proving any one lets you prove the other two. The different intuitions we have about the three statements is part of the reason why some mathematicians hold that they are constructions of the human mind, rather than objective facts about the world. ↩︎

Return to post.